It will be hard, James, but you come from sturdy, peasant stock, men who picked cotton and dammed rivers and built railroads, and, in the teeth of the most terrifying odds, achieved an unassailable and monumental dignity. You come from a long line of great poets, some of the greatest poets since Homer. One of them said, The very time I thought I was lost, My dungeon shook and my chains fell off — The Fire Next Time , James Baldwin

I want to open this by saying that we should be centering black voices in the struggle for racial equality. Without the lived experience to properly inform my judgment, I stand to the side and offer what I can: my time and my voice to amplify black ones. You could skip my babble and just go read this work by a member of the black literary pantheon. With that being said, I hope you enjoy or even learn a thing or two.

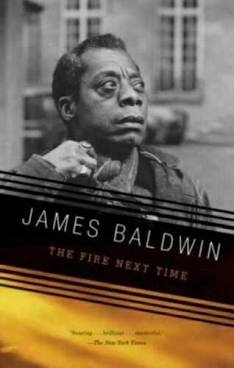

James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time tragically and thankfully stands the test of time. Written in the 1960s in a time when legalized segregation was welcomed with open arms, Baldwin’s lived experiences surrounding race compelled him to write this collection of two essays. Tragically, although some of the overtly outward manifestations of them may have changed, many of the same searing truths Baldwin wrote about 60 years ago still ring bone-chillingly true. Thankfully, his words, imbued with cutting genius and unbridled perception, also still brim with the same potential to hopefully set our minds, and our country, free from the haunting ramifications of racism.

The first essay, titled “My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation,” is ostensibly a letter from Baldwin to his 15-year-old nephew preparing him for the lifelong struggle that is the life of a black American. But beyond his nephew, Baldwin’s words are for us all. The author’s unwavering voice takes up the duel tasks of naming the tangled myriad of ways in which America has designed to deprive its black citizens of their basic humanity, while also trying to giving his nephew, and us, the hope of a brighter future. In Baldwin’s writing, I read a tone of unresigned desperation; Baldwin wants his nephew to not be disillusioned with the painful reality of black life in America, but he also harbors a strong belief that the wisdom he has garnered over the years can lend his nephew the insight to save his own soul.

The second section of the book is called “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” and follows Baldwin through his personal struggle with faith, especially how it intersects with race. He grapples with his upbringing in the Christian congregations of Harlem and the enigmatic curiosity of the Nation of Islam. The voice of the memoir treads cautiously and thoughtfully through the trepidatious terrain that surrounds a religion that proclaims the unqualified humanity of black peoples, and also hosted a rally alongside neo-Nazis. He documents his personal struggle with the ideologies of Elijah Muhammed and Malcolm X; the two leaders of a movement that condemns white folks with the same venom as one would the devil.

Over the course of both essays, Baldwin engages with the concepts of humanity, religion, family, and nationality─all facets of identity. But, critically, he always returns to center his discussion upon the unignorable construct of race. There is something here for every reader: from the brave, wounded victims of 400 years of systemic violence to the “white liberal” of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail to everyone between and beyond. James Baldwin’s haunting warnings to his nephew either remain entirely intact, as if frozen in time by those who stand to benefit the most, or have transmuted to be sufficiently palatable to our modern society─neither have lost any of their vehemence or violent capacity. Reading Baldwin won’t unshackle our country from the scourge of racism, but it is a way to shake our own dungeons and to start ourselves down the path of freeing our own minds from the chains of ignorance.